Conquering Veils: Gender and Islams

by Asma T. Uddin

by Asma T. Uddin

|

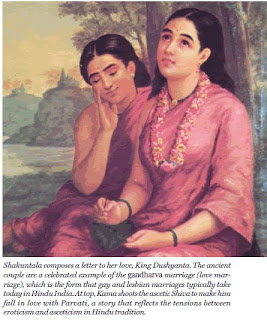

| Photo:1 |

Spiritual evolution works like a standardized test taken on the computer. Every time you get a question right, the computer moves you on to a harder question. But if you get it wrong, it moves you to an easier question. Similarly, if you interpret God’s signs correctly, a veil is lifted, and you comprehend God and the purpose of life more clearly. With each “right answer,” you see more signs and keep moving to the next level of increased revelation and awareness. Eventually, you encounter reality. The final veil to be lifted is that which covers the face of your beloved in the hereafter.

Although I have a long way to go and many more veils to conquer, the struggles of my life thus far have resulted in at least a few “right answers,” evidenced by a spiritual peace previously unimaginable. During some of these struggles, it was less than obvious that I was anywhere near the right answer. Inner turmoil and severe cognitive dissonance — to the point where I felt myself teetering on the precipice between faith and unbelief — convinced me that my inquisitive mind was going to be the end of me.

In the Qur’an, God admonishes us to reflect. Sometimes, reflection brings anguish. It can take us through complex mazes we never really escape until we are ready to move beyond the maze to a greater challenge.

In the Qur’an, God admonishes us to reflect. Sometimes, reflection brings anguish. It can take us through complex mazes we never really escape until we are ready to move beyond the maze to a greater challenge.

|

| Photo: 2 |

My simultaneous encounter with Muslim extremism and a feminist realization of self is one of the more philosophical mazes I have encountered. I spent my youth enchanted by a relatively warm and fuzzy Islam. In middle school, my enthusiasm and love for my religion made me an unintentional proselytizer. By high school, I was studying comparative religion. When the news vilified Islam, I defended it passionately, writing manifestos against the manipulative media representations of Islam.

|

| Photo: 3 |

I eventually recognized this concept of Islam was naive. Moving past it required a lot of tumultuous soul-searching. The journey began when I entered college, where I was assaulted by Muslim extremism. Countless pamphlets extolling the virtues of simplistic Wahhabi thinking floated around the university campus. Books outlining this ideology were stacked up in the prayer room, and the fiery Friday sermons embodied the intense anger behind those words.

feminist

Some of these books were written for women by men, purporting to discuss Islam’s mandates on various women’s issues. The books spoke of women only in terms of subjugation. My innocence was ravaged by the descriptions of women as sex slaves; house servants; satanic temptations; and moral, physical, and intellectual inferiors. The books claimed Islam required these roles for women and that any resistance to this destiny was a sign of impiety — ensuring those women were headed to an indescribably horrid hell.

As I read these books, my identity as a woman was, for the first time, clashing with my Muslim identity. It occurred to me that what I wanted as a woman may not fit with what I wanted as a Muslim. The more I researched the matter, the worse the dilemma became. Islam detractors come in many forms, with some more purposefully destructive than others. When I googled “Islam + women,” I stumbled across endless scores of Islamic texts quoted out of context, mistranslated, or citing weak hadith (oral traditions relating to the words and deeds of the prophet Muhammad). The websites argued that these mangled quotes constituted Islam’s view of women. At the time, I believed them. After all, they were quoting prophetic traditions and other religious texts. How could they be anything but Islamic?

The practical effects of this turmoil were many. Representative of them was my struggle with the hijab, which I had always told myself I would start wearing when I began college — a promise to which I stayed true. It was unfortunate that my adoption of the hijab coincided with my naiveté being shattered by extremist rhetoric. The pride I felt when I wore it was often penetrated by the fact that there were other Muslim women who were being forced to wear it to satisfy some male’s whim.

For those women, hijab was not a symbol of independence and liberation, but precisely the opposite. It held them down, suppressed their individuality, and made them compliant to another’s will. And these women were not just abstract figures described in a textbook. I ran into them frequently around school and at social gatherings, where they were almost uniformly timid, slinking back from attention. I knew it was a logical fallacy to equate oppression with hijab — once I adopted it, I wore it for many years, and in subsequent years, I have met hundreds of incredibly inspirational, strong women in hijab. But at that fragile point in my spiritual growth, observing what was around me, I couldn’t help but increasingly come to fear that my wearing the hijab helped legitimize its use as a tool of subjugation.

Even worse than the male imposition of the hijab was what I call the Hijab Cult, developed by Muslim women in the community. This group ostracized women who didn’t wear hijab, making them feel like lesser Muslims, somehow weaker in their faith than those who wore it. Even though members of this cult were backbiting or constantly judging others’ actions according to their personal rubric of proper Islam, they were still elevated as a symbol for all of those “immodest” women to emulate. The hypocrisy was stifling.

Associating the hijab with harshness, I found my relationship with God was becoming primarily based on fear, rather than being properly balanced between love and fear. I worried incessantly about being judged by Him, and it sometimes felt like His disapproval was manifesting itself in the anger I sensed within my community.

Looking back, I see my plight as a necessary struggle. We all have important causes to which we are innately drawn. My cause has always been twofold: women’s equality and Islam. For the world to make sense to me, women and men had to be of equal worth and dignity, just as Islam had to be the true religion. Before I encountered the extremist interpretation of Islam, my world seemed wonderfully whole. Afterwards, my world became fragmented. To glue it back together, I had to reconcile sex equality and Islamic piety.

It took years for me to achieve any semblance of peace, which came largely through long periods of observation and contemplation of what I later discovered to be God’s signs. He was initiating dialogue, and through time, I came to embrace that interaction. As I continued to read, I encountered a wide variety of books about spiritual purification and other issues beyond the extremist rhetoric. I questioned the reasons behind my feminist bent. Following hours of meditation and, eventually, greater self-realization, I learned to better distinguish between the environmental and instinctual sources of my ethics. And more importantly, I discovered an Islam that was welcoming — similar to my high school Islam, but far richer and more complex than any Islam I had before encountered. For me, the intricacies of Islamic legal interpretation, the depth of Islamic spirituality, and the breadth of Islam’s acceptance of variable practices forever disproved the extremist version.

Whereas before I had always feared subjectivity and variability in religion — mistaking these characteristics as somehow being antithetical to absolute truth — what I learned from my studies of Islamic law and legal interpretation is that subjectivity actually underscores religious authenticity. If Islam, aside from its essential core, is about interpretational diversity — allowing room for people’s cultures and personalities to determine what is religiously “right” or “possible” for them — then there is a greater likelihood that Islam is the true religion. After all, truth must be accessible to all, and universal accessibility is impossible with black-and-white interpretations that place most of the world outside the parameters of “proper” Islam. And it was precisely this that I learned of my religion: Islam is, at its core, a religion of dissent. It is not premised on an endless list of do’s and don’ts but is instead multifarious and openly accepting of multiplicity.

One of the bases of multiplicity is culture. As Dr. Umar Abd-Allah explains in his article “Islam and the Cultural Imperative,” Islam spread throughout the world by adopting the culture of the people it sought to convert. Muslims did not brand these cultures “foreign” and invalidate them in the name of “Islam”; instead, they incorporated everything except those ideas that clearly contradicted Islamic principles and used those elements to make Islam acceptable and, eventually, indispensable to the people. Islam spread when Muslims stayed true to all of the Qur’an’s fundamental principles, including its message of acceptance.

It was precisely this message that helped heal the rupture between my identities as a woman and a Muslim. My understanding of Islam continues to evolve, but it has finally found a solid foundation. As a woman and an American, I have certain values and inclinations that are, at the core, moral. And I had finally encountered an Islam that embraced this core and encouraged me to use it to do good things for myself and others. In realizing these actions would draw me closer to God, I obliterated yet another barrier between Him and me. It was a momentous victory.

feminist

Some of these books were written for women by men, purporting to discuss Islam’s mandates on various women’s issues. The books spoke of women only in terms of subjugation. My innocence was ravaged by the descriptions of women as sex slaves; house servants; satanic temptations; and moral, physical, and intellectual inferiors. The books claimed Islam required these roles for women and that any resistance to this destiny was a sign of impiety — ensuring those women were headed to an indescribably horrid hell.

As I read these books, my identity as a woman was, for the first time, clashing with my Muslim identity. It occurred to me that what I wanted as a woman may not fit with what I wanted as a Muslim. The more I researched the matter, the worse the dilemma became. Islam detractors come in many forms, with some more purposefully destructive than others. When I googled “Islam + women,” I stumbled across endless scores of Islamic texts quoted out of context, mistranslated, or citing weak hadith (oral traditions relating to the words and deeds of the prophet Muhammad). The websites argued that these mangled quotes constituted Islam’s view of women. At the time, I believed them. After all, they were quoting prophetic traditions and other religious texts. How could they be anything but Islamic?

The practical effects of this turmoil were many. Representative of them was my struggle with the hijab, which I had always told myself I would start wearing when I began college — a promise to which I stayed true. It was unfortunate that my adoption of the hijab coincided with my naiveté being shattered by extremist rhetoric. The pride I felt when I wore it was often penetrated by the fact that there were other Muslim women who were being forced to wear it to satisfy some male’s whim.

For those women, hijab was not a symbol of independence and liberation, but precisely the opposite. It held them down, suppressed their individuality, and made them compliant to another’s will. And these women were not just abstract figures described in a textbook. I ran into them frequently around school and at social gatherings, where they were almost uniformly timid, slinking back from attention. I knew it was a logical fallacy to equate oppression with hijab — once I adopted it, I wore it for many years, and in subsequent years, I have met hundreds of incredibly inspirational, strong women in hijab. But at that fragile point in my spiritual growth, observing what was around me, I couldn’t help but increasingly come to fear that my wearing the hijab helped legitimize its use as a tool of subjugation.

Even worse than the male imposition of the hijab was what I call the Hijab Cult, developed by Muslim women in the community. This group ostracized women who didn’t wear hijab, making them feel like lesser Muslims, somehow weaker in their faith than those who wore it. Even though members of this cult were backbiting or constantly judging others’ actions according to their personal rubric of proper Islam, they were still elevated as a symbol for all of those “immodest” women to emulate. The hypocrisy was stifling.

Associating the hijab with harshness, I found my relationship with God was becoming primarily based on fear, rather than being properly balanced between love and fear. I worried incessantly about being judged by Him, and it sometimes felt like His disapproval was manifesting itself in the anger I sensed within my community.

Looking back, I see my plight as a necessary struggle. We all have important causes to which we are innately drawn. My cause has always been twofold: women’s equality and Islam. For the world to make sense to me, women and men had to be of equal worth and dignity, just as Islam had to be the true religion. Before I encountered the extremist interpretation of Islam, my world seemed wonderfully whole. Afterwards, my world became fragmented. To glue it back together, I had to reconcile sex equality and Islamic piety.

It took years for me to achieve any semblance of peace, which came largely through long periods of observation and contemplation of what I later discovered to be God’s signs. He was initiating dialogue, and through time, I came to embrace that interaction. As I continued to read, I encountered a wide variety of books about spiritual purification and other issues beyond the extremist rhetoric. I questioned the reasons behind my feminist bent. Following hours of meditation and, eventually, greater self-realization, I learned to better distinguish between the environmental and instinctual sources of my ethics. And more importantly, I discovered an Islam that was welcoming — similar to my high school Islam, but far richer and more complex than any Islam I had before encountered. For me, the intricacies of Islamic legal interpretation, the depth of Islamic spirituality, and the breadth of Islam’s acceptance of variable practices forever disproved the extremist version.

Whereas before I had always feared subjectivity and variability in religion — mistaking these characteristics as somehow being antithetical to absolute truth — what I learned from my studies of Islamic law and legal interpretation is that subjectivity actually underscores religious authenticity. If Islam, aside from its essential core, is about interpretational diversity — allowing room for people’s cultures and personalities to determine what is religiously “right” or “possible” for them — then there is a greater likelihood that Islam is the true religion. After all, truth must be accessible to all, and universal accessibility is impossible with black-and-white interpretations that place most of the world outside the parameters of “proper” Islam. And it was precisely this that I learned of my religion: Islam is, at its core, a religion of dissent. It is not premised on an endless list of do’s and don’ts but is instead multifarious and openly accepting of multiplicity.

One of the bases of multiplicity is culture. As Dr. Umar Abd-Allah explains in his article “Islam and the Cultural Imperative,” Islam spread throughout the world by adopting the culture of the people it sought to convert. Muslims did not brand these cultures “foreign” and invalidate them in the name of “Islam”; instead, they incorporated everything except those ideas that clearly contradicted Islamic principles and used those elements to make Islam acceptable and, eventually, indispensable to the people. Islam spread when Muslims stayed true to all of the Qur’an’s fundamental principles, including its message of acceptance.

It was precisely this message that helped heal the rupture between my identities as a woman and a Muslim. My understanding of Islam continues to evolve, but it has finally found a solid foundation. As a woman and an American, I have certain values and inclinations that are, at the core, moral. And I had finally encountered an Islam that embraced this core and encouraged me to use it to do good things for myself and others. In realizing these actions would draw me closer to God, I obliterated yet another barrier between Him and me. It was a momentous victory.

Photo:1: "I knew it was a logical fallacy to equate oppression with hijab," the author writes. Here, a feminist marches in the Minneapolis May Day parade in 2006. Creative Commons/Laggard.

Photo: 2: AltMuslimah.org.

Photo: 3: A mural outside Daniel's tomb in Shush, Iran, calls on women to veil themselves. Credit: Wikimedia Commons/Pentocelo. Note: Asma T. Uddin is the founder and editor-in-chief of altmuslimah.com. She is also an international law attorney with The Becket Fund for Religious Liberty, a public interest law firm based in Washington, DC.

Source: Tikkun