The Great Nastik Revolt

~~ by Prabhakar Kamath

Intellectual Ferment: By 600 B.C.E. a great intellectual ferment was brewing across the Indo-Gangetic plain the likes of which India has not seen since. Countless different Kshatriya-inspired philosophies sprang up from the agitated intellect of the Indo-Gangetic Civilization. During this period (900-500 B.C.E), thousands of wandering sophists, known as Parivrajaka, crisscrossed the country questioning anything and everything, including the doctrines of the Gunas and Karma, the Vedas, Vedic sacrificial rites, animal sacrifices, Varna Dharma, and supremacy of Brahmins. They engaged each other in robust public debates on every topic on earth. They challenged their adversaries to either win them over in debate or to follow them. These ‘argumentative Indians‘ came to be known as ‘ ‘Hair splitters’ or ‘Eel wigglers.’ The public halls all over Aryavarta were packed with curious people eager to learn and experiment with new ideas to cope with life’s vicissitudes. New Age Philosophies thrived everywhere. They were all sick and tired of Brahmanism’s remedy for every problem in the world: Perform sacrifices!

The Rise Of Heterodox Dharmas:

This was the period in India’s history when massive winds of change were blowing through the land resulting in the overthrow of the decaying old social, political, and religious orders. Disgusted and disenchanted by Brahmanism, the opposition gradually coalesced into a number of reactionary groups over the centuries following the Vedic period. These reactionaries could be broadly classified into two groups: The Upanishadic sages, who attempted to reform Brahmanism from within (as we studied in the previous article), and Nastiks, nonbelievers, who rejected the essential elements of Brahmanic Dharma, and abandoned it altogether. Those days the epithet Nastik did not mean Atheism since the concept of God was still very nebulous. The Upanishadic entity Brahman, being free from any positive attributes, did not qualify to be a true God. Kshatriya nobles led the heterodox groups just as they did the Upanishadic effort to reform Brahmanism.

Two Nastik Groups:

Within the Nastik movement itself there were two distinct groups: Sramanas (monks) who renounced worldly pleasures, and Lokayatas (worldly) who embraced them. A detailed discussion of the principles of these groups is beyond the scope of this article. The main purpose of this article is to show how they arose in reaction to the decadence of Brahmanism and what their legacies are and what lessons we could learn from them.

1. Sramanas: This group resorted to Sanyasa- literally, “throwing down”- and renounced not only all material comforts but also all socially obligated duties (Karma). Within this group, four distinct sub-sects emerged:

|

| Shri Nakoda Jain Temple |

A. Jainism: The first subgroup, following the philosophy of Mahaveera, later on formed Jainism. The hallmark of this religion was absolute nonviolence toward all living things. This religion was clearly reacting to the horrors of animal sacrifices emblematic of Brahmanism. Some of these monks walked around naked as an expression of their complete renunciation of material things and accidental violence against living creatures. Jainism gained many adherents, mostly in the business class. It got a huge boost when Chandragupta Maurya abandoned his throne and joined it in 298 B.C.E. He retired to a Jain hermitage at Shravana (Sramana) Belagola in what is today Karnataka State, and starved himself to death in the manner of Jain saints.

B. Ajivika: The second of these Nastik groups was Ajivika, founded by Gosala, a contemporary of both Mahaveera and the Buddha. This sect believed that everything in this world was predetermined (Niyati). Destiny, not man’s actions, determined the outcome of one’s soul. Their philosophy can be summed in one line: Go with the flow. Chandragupta’s son Bindusara (ruled 298-272 B. C. E), who boasted the title of Amitraghatha, meaning Slayer of Foes, abandoned Brāhmanism and embraced Ajivika sect. He detested Brahmanism and yet he did not care for Buddhism and Jainism as they were too nonviolent to suite his title or temperament. He believed in his destiny as the emperor of the largest empire ever in India. In fact, his empire was larger than present day India, Pakistan and Bangladesh combined!

|

| Mauryan Empire during Ashoka's rule |

C. Buddhism: The third subgroup, following the teachings of Gautama Buddha, later developed into Buddhism. This was essentially a rational Dharma that emphasized right thinking and conduct. Buddhists rejected all aspects of Brahmanism except for the doctrine of Karma. Right conduct, not birth-class, should decide one’s status on life, they said. Morality, not class system and rituals, defines a true Dharma. As we will study in our future articles, Upanishadism and Buddhism had many things in common. The Buddhist monks were known as Bhikkus as they made their living by begging. Beggars became holy and begging became fashionable in India. Buddhism’s Three Fundamental Laws, Four Noble Truths, and Eight Noble Paths arose in reaction to the decadence of Brahmanism. From the Buddhist point of view, man created God to meet deep psychological needs such as to fulfill desires and protection from evil. Buddhism gained royal patronage for nearly 1000 years. Ashoka the Great (ruled 272-232 B.C.E.) abandoned Brahmanism and embraced rationalist Buddhism, which he referred to as the true Dharma (Dhamma). He was singlehandedly responsible for making Buddhism the predominant Dharma of India till the 8th century A.D., and into a World Religion.

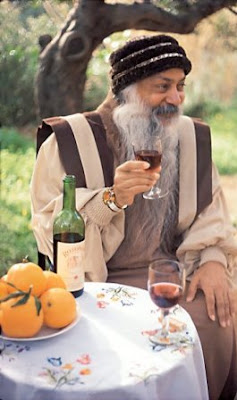

D. Asceticism: The fourth subgroup of Sramanas consisted of individual Ascetics (Munis, the Silent Ones), who renounced everything and wandered in search of the Ultimate Reality. These people often practiced severe austerities (Tapas) in the form of self-denial and self-torture as the means of mastering their senses to achieve personal liberation from Samsara. Half-naked Sadhus and Sanyasis, who stick long needles into their tongue and cheeks; who hang from trees by means of hooks, and who stand on one leg for years, belong to this subgroup (BG: 17:5-6). We can find true as well as false Ascetics, Swamis and Gurus such as these all over India and abroad to this day.

Dharma of Brahmanism versus Dharma of Buddhism:

Both Brahmanas and Buddhists used the term Dharma to promote their own agendas. To Brahmins, Dharma meant people of each class (Varna) faithfully and helplessly performing their class-designated duties as per their specific Guna (Sattva, Rajas, etc.). For example, a Kshatriya’s Dharma was to invade his enemy’s territory, steal his cows, burn his buildings, kill him and acquire his wealth. This was exactly what Ashoka did when he invaded Kalinga. To emphasize this, prince Krishna often addresses Arjuna as Dhananjaya (Conqueror of Wealth, BG: 1:15) and Paranthapa (Scorcher of Foes, BG: 2:3), and Arjuna addresses Krishna as Madhusoodana (Slayer of Madhu) and Arisoodana (Slayer of Foes, BG: 2:4). If a Kshatriya refused to fight for a ‘righteous cause’, whatever that phrase meant, then he was considered as one who had abandoned his Kshatriya duty, as did Arjuna in the Original Gita, before he was brought to his senses by prince Krishna. Such a Kshatriya was described as unmanly, impotent, cowardly, dishonorable, and the like (BG: 2-3). He would suffer dishonor in the society here on earth and hell hereafter (BG: 2:33). There was no room for compassion, mercy, kindness, etc. when a Kshatriya performed his Dharma. And it did not matter who the identified enemy was -Guru, uncle, great uncle, grandfather, cousins- one must give up his Ahamkara (I, me and mine) and perform his Dharma as defined by his Varna. No guilt or sin would arise from such actions (BG: 18:17). Likewise, a Brahmin’s Dharma was to chant the Vedic hymns, perform Yajnas, kill animals and sacrifice them in the fire to please the gods. Their logic was that all Dharmas are attended with some evil like smoke enveloping fire; that is no reason to abandon them (BG: 18:48). It is better to perform one’s own Dharma imperfectly than to perform another’s perfectly because in the former case one goes to heaven and in the latter case one goes to hell (3:35). The ultimate goal of all classes was to gain perfection here on earth by performing faithfully and helplessly his class-designated Dharma (BG: 18:45). Therein lay the stability of the society -and supremacy of Brahmins in the Varna system.

To Buddhists, on the contrary, Dharma meant ethical principles such as nonviolence, truthfulness, generosity, kindness, tolerance, equality, goodness and mercy, which people of all classes should practice. The Dhamma (ethics) of a Brahmin should not be different from that of a Sudra. In fact, such class distinction should not exist at all. Furthermore, one must respect sanctity of life and not kill animals for the sake of sacrifice. Even burning rice kernel with chaff was not good. To them Vedic rituals were useless as compared to the practice of ethics. Ashoka says:

Rock Edict # 9: Other ceremonies (rituals of Brahmanism) are of doubtful fruit, for they may achieve their purpose, or they may not, and even if they do, it is only in this world. But the ceremony (practice) of Dhamma is timeless. Even if it does not achieve its purpose in this world, it produces great merit in the next, whereas if it does achieve its purpose in this world, one gets great merit (here on earth) and there (in heaven) through the ceremony (proper practice) of the Dhamma.

2. Lokayata: The second major Nastik reactionary group, known as the Lokayatas, also known as Charvakas or Materialists, went in the opposite direction. The most prominent Lokayata philosopher was Brihaspati who lived around 600 B. C. E. We can get glimpses of this great man’s thinking from a quote in Madhvacharya’s Sarva Darshana Samgraha (early 14th century):

“There is no heaven, no final liberation, nor any soul in another world, nor do the actions of four castes, orders, etc. produce any real effect. The Agnihotra, the three Vedas, the ascetic’s three staves, and smearing one’s self with ashes, were made by nature as the livelihood of those destitute of knowledge and manliness. If a beast slain in the Jyotisthoma rite will itself go to heaven, why then does not the sacrificer forthwith offer his own father? If the Shraddha produces gratification to beings who are dead, then here, too, in the case of travelers when they start, it is needless to give provisions for the journey… While life remains let man live happily, let him feed on ghee even though he runs in debt; when once the body becomes ashes, how can it ever return again? If he who departs from the body goes to another world, how is it that he comes not back again, restless for love of his kindred? Hence it is only as a means of livelihood that Brahmins have established here all these ceremonies for the dead, -there is no other fruit anywhere…”

The amazing thing about the above statement is that this man, who lived 2600 years ago, appears to be so modern and rational in his thinking! If we met this man in the street today, we might have a conversation with him like we would with an enlightened man of 21st century. As regards living on borrowed money, which I think was a rhetorical statement, I am sure there are a lot of followers of this particular aspect of Lokayata philosophy all over the world.

Legacy Of, And Lessons From, Sramana Sects:

Jainism: Jainism has lingered on as a minor religion in India to this day, patronized over the centuries by minor royal houses and rich merchant class in the western and southern India. Jainism did not have a great royal patron like Buddhism did in Ashoka the Great. Jainism did not pose a significant threat to Brahmanism and so it has survived in India to this day. Even though a minor religion, the influence of Jainism on Brahmanism and the rest of the world was as profound as Buddhism, if not more. It was Jain philosophy of Ahimsa (nonviolence), which led to Brahmanism finally giving up animal sacrifices and embracing vegetarianism. Mahatma Gandhi’s Satyagraha movement during India’s independence struggle was rooted in the Jain philosophy of nonviolence. Dr. Martin Luther King’s successful struggle to emancipate African-Americans in America was patterned after Gandhi’s nonviolent method in India.

Ajivika: Ajivika sect lingered on till 13th century and met its Destiny in the dustbin of history thereafter. However, its theory of Destiny (Niyati), which is often interpreted as fatalism, occupies the intellect of many Indians to this day. We can frequently get glimpses of Ajivika philosophy in conversations with Indians: “No one can change one’s Destiny.” “Whatever is destined to happen, will happen.” “All this is a play of Fate!” “Whatever is written on your forehead cannot be changed!” Complete acceptance of Destiny gives one complete peace of mind as well as absolute passivity!

|

| Young Monks |

Buddhism: For 1000 years after the Buddha’s death, Buddhism spread in leaps and bounds under the patronage of great royal houses: Maurya, Greco-Bactrian, Kushana, Gupta, Maukhari, Pala and the like. Resurgence of Brahmanism began in the early centuries of Christian era, probably under the patronage of the Guptas. By the time of Harshavardhana of the Maukhari house (590-647 A. D.), its lobby was strong enough to attempt his assassination for patronizing Buddhism. Another development that enhanced decline of Buddhism was revival of Brahmanism led by Shankaracharya (788-820 A. D.). He singlehandedly revived Brahmanism from ts deathbed by means of his great intellect, and even greater gift of the gab, and perhaps the greatest duplicity of all the Acharyas in interpreting anti-Brahmanic literature such as the Upanishads and the Bhagavad Gita. In the course of our quest for truth, we will study some examples of his deliberate misinterpretations and nonsensical commentaries on the anti-Brahmanic shlokas of the Bhagavad Gita. By doing so, he converted the Bhagavad Gita, ‘The Manifesto of the Revolution to Overthrow Brahmanism’, into ‘The Standard Handbook of Brahmanism’. After the arrival and spread of Islam (10th -12th A. D.), Buddhism disappeared from India altogether. Brahmanism absorbed what little was left of it and half-heartedly declared the Buddha as the ninth avatara of Vishnu. A section of Brahmanism continued to vilify him as one born to mislead Nastiks to hell. Regardless, Buddhism became the World Religion, thanks to two great Chinese pilgrims to India and innumerable Bhikkus who spread the message of the Buddha all over Far East and Middle East. I will not be surprised if some day some open-minded Christian scholar will trace the origin of Jesus’ ‘show him the other cheek’ philosophy to that of the Buddha, exported to Middle East by Ashoka’s emissaries in the 3rd century B. C. E. In fact, Jesus’ revolt against Orthodox Judaism, and subsequent birth of Christianity, followed the blueprint laid by the Buddha.

Legacy And Lessons From Sramanas:

The lesson to be learned from all the above Sramana sects is that any attempt to bring sanity into Brahmanic Dharma should be characterized by purity of purpose, speech, thought and action. The rationalist activist must be perceived by his target population as a person who is rational, reasonable, good, honest, nonviolent and free from common human weaknesses such as anger, hatred, greed, selfishness, arrogance, and deceitfulness. Nothing hurts a reform movement like the perception by the target population that the activist himself is not of exemplary behavior. In other words, all reformation movements are nothing but exercise in self-improvement. Without trust in the reformer’s bona fides, his attempts will not bear any fruits. A rationalist’s approach should be one in which he comes across as genuinely interested in helping the religionists in overcoming their irrational fears and insecurities, which are the basis of their irrational beliefs and behaviors. This reminds me of the anecdote in which a psychotic patient tells his psychiatrist that he lives on the moon. The psychiatrist empathically plays along and even accepts the patient’s invitation to visit him on the moon on a certain date. On the designated day of the visit to moon, the psychiatrist says, “All right, I am ready. Let us go.” The patient surprises the psychiatrist by asking him, “You mean you really believe that I live on moon?”

Lesson From Lokayatas:

Lokayata philosophy was largely misunderstood, ridiculed and hooted off the Indian stage of philosophy by Brahmins as it struck at their very livelihood. Most of what we know of its fundamental beliefs comes to us from its staunch Brahmanic critics, and therefore is of dubious value. Many of their tenets were deliberately or out of ignorance misinterpreted by Brahmanic commentators. Its literature was available to scholars at least till 17th century. It disappeared entirely over the past few centuries. Either Brahmanic loyalists destroyed it, or the palm leaves rotted away or were eaten by termites. Prakriti has a way of destroying everything, especially in India!

As the reader can discern, the Lokayata philosophers did not mince words. They indulged in frontal attacks against what they considered as Brahmanic fraud. However, frontal attacks, such as those launched by the Lokayatas against essentially irrational beliefs of Brahmanism rarely, if ever, get desired results. Logic, facts, and reasoning are no match to deep-rooted beliefs of delusional proportion, which majority of Hindus have. When Mahmud of Ghazni stormed the temple of Somanatha in 1025 A. D., he found 50,000 deluded Brahmins and devotees crying with their hands wrapped around their necks and repeatedly pleading with the stone lingam (phallus) of Shiva to save them as well as their rich temple from the sword of Mahmud. Mahmud, though no less deluded by his own religion, had more faith in his own sword. He gladly obliged the Brahmins and devotees to chop their bobbing heads off. Till the last man the devotees refused to believe that the stone lingam had no power to protect them. It didn’t occur to their deluded intellect that if the Shiva lingam did not save them from Mahmud’s sword after one pleading, repeat pleadings would not make any difference. Such is the deluding effect of religion on one’s reasoning powers.

Changing Beliefs And Behaviors Is A Mighty Task:

Man is essentially a creature of well-established beliefs, habits and behavioral patterns and it is mighty hard to change these. For example, people, who are always late for parties, as is the case with the vast majority of Indians I know in America, rarely change their behavior no matter how well one reasons with them. When confronted, they give one or more totally irrational explanations for their tardiness. They might need a combination of insight into their unconscious belief system (such as “I have to keep my ‘dignity’ by showing up late”, or, “If I show up on time my host might think I am dying to eat his food”) and incentive to change (such as “Sorry, all freshly made Jelebis were gone an hour ago! You are too late!” or a note on the door, “Sorry, the party ended an hour ago. We have gone for a walk.”). It takes a lot of mental energy for people to adopt a new belief system (such as “It is a sign of utter disrespect for the host if I don’t show up on time”) and conform their behavior to their new beliefs (such as “I must show up for the party on time”).

Most People Are On Autopilot:

It takes a highly “aware” person to transcend the power of childhood indoctrination and resort to reasoning. Most Hindu religionists I know do not fall in this category. Even a confirmed Atheist might reflexively exclaim “Oh, my God!” when he witnesses a tragedy or when he has an extremely pleasurable experience. That does not make him a believer in God. It simply proves that deep-rooted behaviors are often on autopilot and are very difficult to remove. Very high level of self-awareness and reasoning power are needed for one to change one’s irrational behavior. As a psychiatrist, I can attest to the fact that majority of my highly educated patients are unable to change their well-established behavioral patterns in spite of many attempts and reminders even in the context of a trusting relationship.